TENDINOPATHY: WHAT IS IT?, COMMON PRESENTATIONS AND THE ROLE OF MYOTHERAPY

Tendinopathy is a term used to describe pathology of a tendon. This pathology can arise for various reasons with a common belief being that inflammation was a major cause of pain and dysfunction. This lead to the use of a term you may be familiar with, tendinitis, which has commonly been used to describe pain affecting tendons (Achilles tendinitis, patellar tendinitis etc).

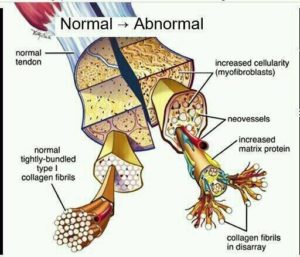

However, for many years now the consensus is that this is an outdated term due to the fact there is rarely inflammation, or at least abnormal levels of inflammation, found within a tendon when it becomes dysfunctional. Research is now indicating that degeneration and disruption of the collagen fibres within a tendon is the main issue and that if inflammation is present it is more likely to be a secondary response to the degeneration and not the other way around.

Therefore, it has been suggested, the suffix, –itis, should no longer be used and replaced by the suffix, -osis, which typically means ‘an abnormal state or condition’. For the purposes of this blog, whilst there is still some conjecture regarding the definition, we will be referring to everything as tendinopathy.

Why is the terminology important?

Whilst it is important to be describing something correctly that is not the main reason why clinicians need to get it right. The treatment protocol and prognosis differs depending on what you feel is causing the issue. For example, research indicates that the use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) or cortisone injections in managing the management of tendinopathy can have a negative effect as it slows down the rate of new tendon cell growth. This goes against the common treatment which was to advise patients’ to take NSAIDS at the first sign of pain in an attempt to get rid of the inflammation. If the issue is degenerative, disorganised collagen then the treatment needs to be focused on rehabilitating that tendon; research indicates you should expect this process to take many months which is important in reducing the inevitable frustration if you don’t see improvement quickly.

What are the causes and signs of tendinopathy?

Tendons are highly adaptable and strong but can also be quite fickle. Tendons respond to load or stresses placed on them; but if the capacity of the tendon is outweighed by the load then a dysfunctional tendon will likely arise. Tendons also do not like to be compressed or stretched for long periods, which is unfortunate, because it is very easy to do. If you are sitting reading this you are compressing both of your proximal hamstring tendons, and if you’re sitting with crossed legs you are compressing your gluteal tendons as well.

Tendinopathy is distinguished primarily by pain at the site of the affected tendon. Other common features are:

– stiffness at the site that eases with activity;

– increased pain the more you do;

– loss of strength at the affected area;

– crepitus and restricted movement in the surrounding joints; and,

– a history that correlates; e.g. stop-start activities or jumping for patellar tendinopathy or simply being in the right age group (>40) and gender (female) with hip pain that points to gluteal tendinopathy.

What are some common tendinopathies that Myotherapists manage?

Any tendon in the body has the potential to become dysfunctional and painful, with 3 examples being:

– Gluteal tendinopathy: Pain will likely be on the lateral aspect (outside) of the hip and most commonly affects women over 40 years of age. Sufferers describe the pain as a constant ache/bruised sensation that is worse in the morning, using stairs and standing up from a chair. Risk factors, besides age and gender, are anything that increases hip adduction including side-sleeping, sitting with one leg crossed over the other knee, standing with hitched hip, going upstairs (if strength deficits) and a wide hip (Q) angle.

– Hamstring tendinopathy: Pain will likely be in the middle of the lower buttock right where you sit and is typically worse after activities involving running, lunging, squatting or prolonged sitting as these movements increase the tensile and compressive loads on the tendon.

– Patellar tendinopathy: Pain will be localised to the insertion of the patellar tendon onto the tibia and the tendon can be visibly thicker when compared to the unaffected side. Risk factors include activities involving jumping, kicking and rapid changes in directions (cutting manoeuvres) and this pain will typically feel worse going downstairs.

How do you treat tendinopathy?

At a basic level, removing the aspects which may have caused the tendinopathy is the key to rehabilitation. Initially, this involves removing the aggravating factors and treating the pain through massage, myofascial release, joint mobilisation, and sometimes dry needling to affected muscles. Once the aggravating factors have been removed then the focus shifts to strengthening the tendon and surrounding structures. At this point, it is important to acknowledge that the current thinking is that once a tendon is deranged/degenerated then that part will remain that way; what we are trying to do is increase the capacity of the healthy part of the tendon and the structures around that area to withstand the load placed on it… and the best way to do that? By loading the tendon progressively to increase the strength and endurance of the damaged tissue.

So let’s look at our examples above:

– Gluteal tendinopathy: Initially, focus will be on reducing the compressive loads on the tendon by sitting with your knees apart, standing on two legs (weight in the middle) at all times, and sleeping in positions that do not load the lateral hip. Then it will be important to strengthen the gluteal muscles and surrounding muscles involved with stabilising the pelvis via static hip abduction, bridge, double leg squats, weighted squats, crab walks, step-ups etc.

– Hamstring tendinopathy: Avoiding lunges, squats, running (particularly uphill) and prolonged sitting will help to reduce the load on the hamstring tendon, but don’t worry you will get back to doing those exercises again… just when the tendon is ready for that level of load. Then moving through a range of exercises including bridges, planks, hamstring curls, dead lifts etc will increase the load bearing capabilities of the muscles/tendons around the damaged tissue.

– Patellar tendinopathy: For as short a time as possible, any aggravating factors should be stopped to allow tendon healing (walking downstairs, playing sports involving jumping). Then progressing through body-weight squats, weighted squats, leg press and knee extension exercises will reduce the risk of recurrence.

With all these exercises it is okay to experience some discomfort during and after completing them but if the increased pain lasts longer than 24 hours then adjustments need to be made. For this reason, it is important that a qualified practitioner develops the plan but also monitors the plan.

Myotherapists are experts in managing these types of issues as they are well trained in the use of manual therapy, dry needling and joint mobilisation to alleviate pain but can also develop a tailored treatment program and guide you through the rehabilitation process.

If you think you may be suffering any of the above conditions or have any other upper/lower limb or back pain then book an appointment today. For further info or to book an appointment call 94805522 or book online at www.northernpodiatry.com.au

By Travis Robertson

0